Offcuts

Offcuts: We Will Endure

THE Australian farming community is renowned for its resilience.

And let's be honest, you've needed every little bit of it to navigate the seemingly endless number of hurdles thrown at you since the calendar ticked over to January 1, 2020 (and before).

Even before the acronym COVID‑19 became part of the common vernacular, rural Australia felt the full wrath of Mother Nature in the form of drought, fire and floods.

On a personal level, our collective hearts broke at Quality HQ watching the scenes of devastation as bushfires ravaged the country and personally affected several our clients and friends.

The image beamed around the nation of a

It's easy to spout platitudes like ''we'll get through this" and "short‑term pain for long‑term gain", but for those feeling the pinch of the coronavirus and struggling to see light at the end of the tunnel, this might feel out of reach right now.

However, a quick glance through history outlines a precedent that might provide a small degree of comfort to our farming community.

Whether it be a recession, a global health crisis or a war, Agriculture has proven itself to be an extremely stoic industry, at the very least capable of sustaining itself and weathering the storm and in some instances, actually thriving or playing a key role in recovery.

Here's a list of occasions throughout history when Australian agriculture has

The First World

The outbreak of war in August 1914 was generally disastrous for the Australian

The golden fleece was one of a select few Australian commodities which was purchased by the British government and essentially kept the country afloat.

As outlined in more detail in a previous edition of this column (Wool still on the front line: https://bit.ly/2UiEvh7), Australian wool growers had a near monopoly of world production at the time and only they could supply the wool needed for clothes, uniforms, and blankets for the war effort.

This was briefly threatened in February 1916 when the British government asked Australia to stop all wool exports except to Britain, leading to a steep fall in wool prices.

However, after lengthy negotiations during a visit by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes to the UK in 1916, the British government agreed to buy Australia’s entire wool production for the remainder of the war at a price 55 per cent above the pre‑war average.

This proved to be an enormous financial windfall for a country under severe economic strain.

The Great

The Great Depression was the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialised world, lasting from 1929 to 1939.

And it also highlighted Australia’s reliance on wool exports at the time in both a positive and negative fashion.

Valued at 66 million pounds ($132 million) in gold in 1928/29, Australia’s wool exports fell to 36.5 million pounds ($73 million) in 1929/30 and 32 million pounds ($64 million) in 1930/31 as the depression took the globe in its grip.

Ironically, while the decreased value of Australia’s biggest export product was a prime cause of the economic depression that almost broke Australia in the early 1930s, it also kept the country on life support during this period.

Wool provided around a third of the country’s export income in the depressed years of the early 1930s, increasing to 45% in 1936.

By this time, Australian wool was directly responsible for the welfare of up to 20% of the Australian population.

This gives new meaning to the phrase “thank a farmer for your next meal”.

Introduced from Europe in the 1850s, rabbits had reached plague‑levels of 10 billion in Australia by 1920 and threatened to bring Australia’s wool industry to its knees.

Known as the “grey plague”, hunters couldn’t keep up with the extraordinary rate at which rabbits multiplied and soon millions of them were competing with our 100 million‑strong sheep flock for feed.

The grave nature of the situation was summed up by the land editor of the Sunday Herald on January 23, 1949:

“If there is a drought, the rabbits will get most of what feed there is, and we could lose millions of sheep in six months. In one year of such a drought, half our Merino flocks could disappear. This would be a national disaster”.

Thankfully, some of Australia’s biological minds answered the call and soon after, the Myxomatosis virus was introduced to Australia in 1950 to eradicate the plague, initially with great effectiveness (99 per cent eradication in some areas).

Within two years of the introduction of the disease, Australia’s wool and meat production had recovered from the rabbit onslaught to the tune of $68 million.

While the virus has lost some of its effectiveness over time and rabbits remain a persistent pest that costs the wool industry millions each year, intervention in the mid‑20thcentury was crucial to keep the threat at bay.

The Polio Epidemic

In the 1940s and 1950s, polio was one of the most widespread and dreaded childhood diseases in the world.

While the epidemic didn't threaten the wool industry as such, it did inadvertently play a crucial role in easing the suffering and assisting the rehabilitation of those with the disease.

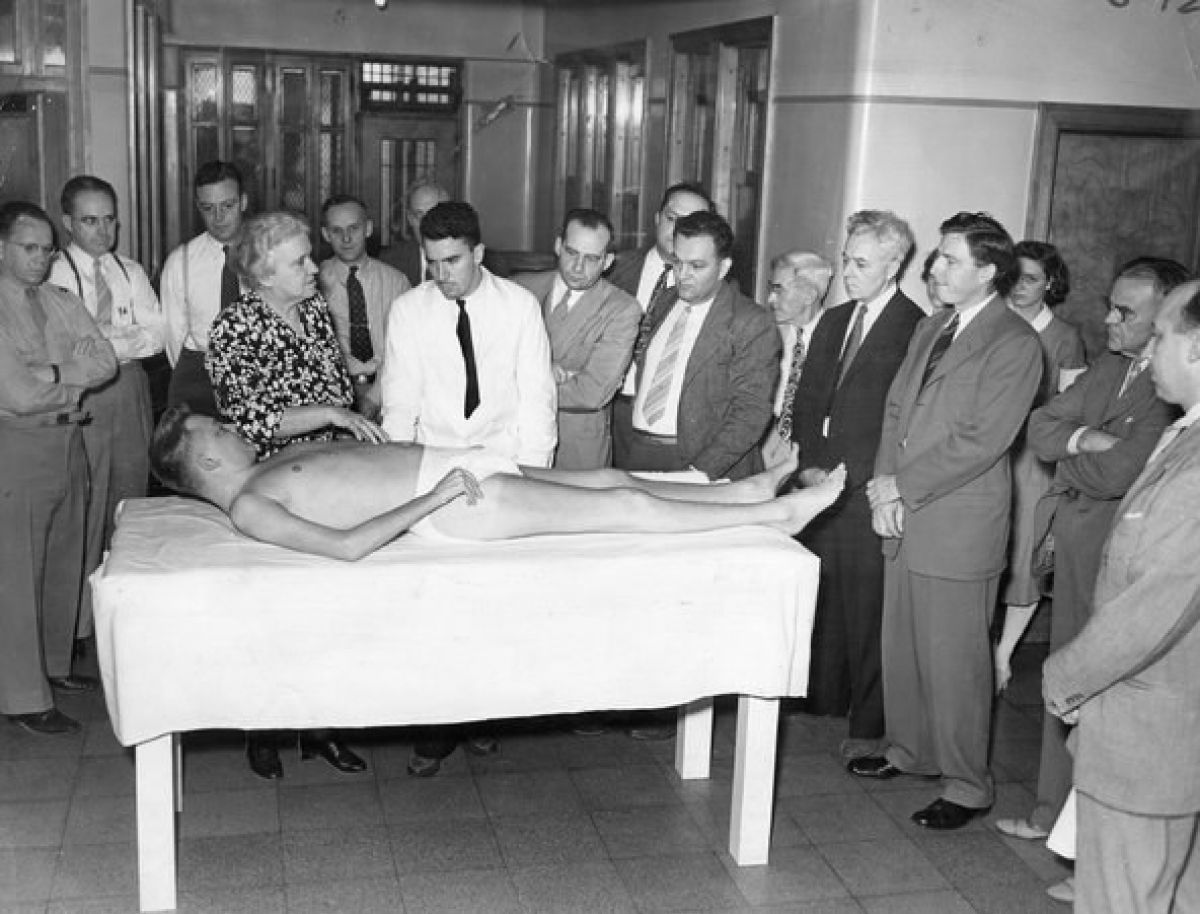

Australian "bush nurse" Elizabeth Kenny, who had no formal medical training, revolutionised the treatment of polio when she discovered that wrapping strips of wool soaked in hot water around paralysed limbs relieved the muscle pain (and combined with muscle exercises, helped to restore function).

This contravened popular medical opinion at the time which called for placing affected limbs in plaster casts.

Kenny's principles of muscle rehabilitation became the foundation of what would later become known as physical therapy (or physiotherapy), and she travelled the world demonstrating her techniques before a polio vaccine was discovered in 1956.

As an aside, while patients who received Kenny’s treatment were extremely grateful, they were also said to rue the smell of wet wool for a long time afterwards!

Modern

The closest thing to what we’re experiencing now was the outbreak of the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) virus, declared an epidemic, between 2002‑04.

Wool industry insiders with reasonably long memories will remember the impact SARS had on the trade at its height in 2003.

With the Chinese government placing restrictions on imports of raw animal products and the movement of people, Australian wool exports fell by 20% in 2002 and by 32% in 2003.

Not surprisingly, our wool exports bounced back to the tune of a 64% spike in 2004 once those restrictions were lifted.

While we’re clouded in uncertainty right now, there are some interesting comparisons to be made between the current situation and the events of 2003.

In the first week of May 2003 when the severity SARS and its impact had on the Chinese economy was hitting home, the Eastern Indicator (EMI) plummeted by 119c to 980c/kg.

This is compared to a 28c/kg drop in the EMI in the final week of January this year (Week 31) as the seriousness of the COVID‑19 outbreak was beginning to be recognised.

Also, Australian shorn wool production was around 500 million kgs in 2003, in contrast to the forecast for 2019/20 which is far lower at 272m kg for 2019‑20.

So will the impact on wool prices be less?

We have our fingers and toes crossed.